|

|

Contact us at: sooddram@gmail.com |

Why

LTTE failed

R. HARIHARAN

Its performance in Eelam War

IV glaringly displayed Prabakaran’s limitations in

mastering the art of conventional warfare.

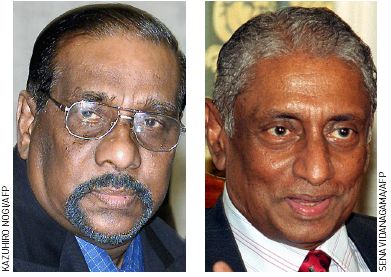

ANTON BALASINGHAM, THE LTTE's political adviser. A 2003 picture. (Right) Lakshman Kadirgamar, the Sri Lankan Foreign Minister who was assassinated in 2005.

SRI LANKA’S security forces appear to have redeemed

their professional reputation with their resounding success in the fourth

edition of the Eelam War, which has been going on

since 2006 against the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam

(LTTE), popularly known as the Tamil Tigers. They were not able to achieve

decisive results against the LTTE in their three earlier outings.

The United States Federal Bureau of Investigation

(FBI) had rated the Tamil Tigers as “among the most dangerous and deadly

extremists in the world”. The FBI said the LTTE’s “ruthless tactics have

inspired terrorist networks worldwide, including Al Qaeda in Iraq”. So, the

security forces’ success against the LTTE should not be underestimated,

particularly when similar wars against insurgents and terrorists in other

countries, including Afghanistan, have been dragging on.

The LTTE, over the past 25 years, has built a

15,000-strong force that innovatively adapted its suicide war tactics to both

land and naval warfare with deadly results. It mastered the use of terror

tactics as a force multiplier. The LTTE’s charismatic and ruthless leader, Velupillai Prabakaran, built a

loyal network of cadre – the Black Tigers – whose deadly suicide terror attacks

changed the course of political history in Sri Lanka and to a certain extent in

India also. Now the insurgents stand reduced to a few hundreds and have lost

their entire territory of over 15,000 square kilometres

and their equipment, weapons, armament and infrastructure so

essential for survival as a viable entity.

The LTTE demonstrated its prowess with a daring

suicide attack on Colombo’s Katunayake international

airport, destroying 26 military and civil aircraft, in July 2001, just four

months before Al Qaeda’s dramatic 9/11 attacks in New York. It sent a strong

message to Sri Lanka and the world at large that the LTTE was a formidable

force not be trifled with. But the consequences of the

9/11 attack on the global attitude to terrorism was far-reaching. The U.S. marshalled forces for a global war on terror to destroy Al

Qaeda and its roots in Islamist terror. And the LTTE was already listed in the

U.S. as a foreign terrorist organisation.

The late Anton Balasingham,

a close confidant of Prabakaran’s and the political

adviser to the LTTE, apparently understood the need to modify the LTTE strategy

in the face of the rising tide against terrorism. He persuaded a reluctant Prabakaran to agree to take part in a Norwegian-mediated

peace process, deferring the idea of an independent Eelam

in favour of finding a solution to accommodate Tamil

aspirations within a federal structure. That was how the 2002 peace process

came into being.

The LTTE signed the Cease Fire Agreement (CFA) with

Sri Lanka in 2002 as part of the peace process from a position of political and

military strength, having weathered four wars – three against Sri Lankan

security forces and one against Indian forces. It was at the pinnacle of its

power at that time. To a certain extent, this enabled the Tamil Tigers to dictate

the terms of the peace process, which recognised it

as the sole representative of the Tamil minority, a status denied to it

earlier. Thus, the peace process accorded parity of status to the LTTE at the

negotiating table in its equation with the elected government of Sri Lanka.

By then, the repeated stories of LTTE successes,

propagated by its well-oiled propaganda machine that glossed over its

significant failures (for example, the retaking of control of Jaffna by the Sri

Lanka Army), reinforced the popular belief of Prabakaran’s

invincibility in war. It also generated great political expectations among the

Tamil population of his ability to satisfy their long-standing aspirations

through the peace process although he had dropped the demand for an independent

Tamil Eelam. All that has been

proved wrong now.

Winston Churchill once remarked, “Those who can win a

war well can rarely make a good peace and those who could make a good peace

would never have won the war.” This is very true in the case of Prabakaran’s handling of events leading up to the war. His

monolithic and egocentric leadership style does not encourage the free exchange

of ideas except with his trusted childhood friends. This has been the big

roadblock in his strategic decision-making process. Prabakaran

failed to use fruitfully the political talent at his disposal, among the

seasoned members of the Tamil National Alliance (TNA), in handling complex

political issues during the period of peace. Their advice was neither sought

nor paid heed to in taking decisions on key issues. The LTTE’s handling of the

presidential poll of 2005 is one such instance when their plea for his support

to elect Ranil Wickremesinghe,

an architect of the peace process, went unheeded.

Wickremesinghe’s rival, Mahinda Rajapaksa,

had promised, in his election manifesto, to eliminate LTTE terrorism. Prabakaran not only ignored this but, on the basis of some

convoluted reasoning, enforced a boycott of the presidential poll in areas

under LTTE control. This action prevented a bulk of the Tamils from voting for Wickremesinghe. This enabled Rajapaksa’s

victory with a wafer-thin majority through southern Sinhala votes. And the

newly elected President went about systematically dismantling the LTTE.

Similarly, Prabakaran’s handling of the international community lacked coherence. Apparently, he misunderstood the international involvement in the 2002 peace process and thought it was a vindication of the LTTE’s methods. Perhaps this made him complacent when it came to observing the ceasefire in spirit. The LTTE’s conduct, which was in utter disregard of international norms on human rights and humanitarian laws during the entire period of the ceasefire, came under severe criticism from international watchdog bodies and the United Nations. These related to a large number of issues, including the recruitment of child soldiers, illegal arrests and kidnapping apart from the assassinations and suicide bombings. This made the LTTE’s rhetoric on human rights hollow.

While the co-chairs were sympathetic to the Tamil

struggle for equity, they were wary of the LTTE’s tactics and covert operations

in their own countries. And the LTTE’s indifference to their counsel during the

peace process eroded its credibility. Things came to a boil with the

assassination of Sri Lankan Foreign Minister Lakshman

Kadirgamar in August 2005. This wanton act compelled

the European Union and Canada to ban the LTTE. Thus, the LTTE shot itself in

the foot as it was banned in 32 countries. The ban also coincided with the

introduction of strong international protocols in shipping and against money

laundering to prevent the international operations of terrorists.

Prabakaran probably failed to appreciate the implications of these developments

when he gave the government a legitimate excuse to abandon the peace process

after the LTTE made an abortive suicide attack in April 2006 on Lieutenant

General Sarath Fonseka, the

Army chief. It also enabled Rajapaksa to persuade the

international community to crack down on the LTTE’s support network and front organisations in their midst. International cooperation was

further enlarged in scope to intelligence sharing and economic aid, which

indirectly underwrote Sri Lanka’s mounting burden of war.

Similarly, Prabakaran never

made any effort before the war to redeem the LTTE’s relations with India. He

failed to tap the fund of sympathy for the Tamil cause that exists in India

even among large sections of the non-Tamil population. Presumably, his dubious

role in Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination prevented him from dispassionately

examining the positive contribution India could have made in pushing the Tamil

cause at the negotiating table. Apparently, he put his faith in the

international community rather than in India to bail him out when the Sri

Lankan government decided to go to war. This showed a lack of understanding of

the complexities of international relations. On the other hand, successive Sri

Lankan Presidents went out of their way to keep India in good humour and that helped the country politically and

militarily in its war with the LTTE. In Eelam War III

(1995-2002), the performance of the Sri Lankan security forces was far from

satisfactory. By then, the LTTE had developed the Sea Tiger wing – a daring

guerilla navy that played havoc with the Sri Lanka Navy. The Sri Lanka Army had

suffered heavy casualties in defending Mullaithivu

and suffered a huge setback in Elephant Pass despite its superior strength and

firepower. In that operation, the LTTE acquired its modern artillery, armour and high-tech communication systems apart from

capturing equipment.

At the start of the peace process, the security forces

were a demoralised lot. The terms of the peace

process further added to their misery as it prevented them from retaliating

when the LTTE’s pistol groups systematically eliminated the forces’

intelligence operatives and killed even military commanders during the first

three years of peace. In this backdrop, no one was sure of the ability of Sri

Lanka’s forces to sustain an offensive against the LTTE when Eelam War IV started in 2006.

Even after the LTTE defeat in Mavil

Aru in the Eastern Province in July 2006, the

security forces were cautious in their optimism. However, the LTTE belied the defence analysts’ expectations when it floundered in the

Eastern Province, offering stiff resistance only in patches. Perhaps, it was at

this time that Rajapaksa and Fonseka

made up their minds to go the whole hog against the LTTE in the north.

Although Prabakaran has

demonstrated strategic military capability in the past, he appears to have

failed to draw two obvious strategic deductions in the developing war scenario,

which put the LTTE at a disadvantage. The first was not factoring the impact of

the defection of Karuna, his able military commander

from Batticaloa, on the LTTE’s overall military

capability. The second was in underestimating the determination of Sri Lanka’s

political and military leadership to turn Rajapaksa’s

promise to eliminate the LTTE into a reality.Prabakaran

never made any effort to patch up with Karuna, who

had grievances with respect to the poor representation of easterners in the

leadership although they provided the bulk of the LTTE cadre. Instead, he

dispatched killers to eliminate Karuna. The rebel

leader commanded wide support among cadre in the east, particularly around LTTE

strongholds in Batticaloa. A direct consequence of

his defection was the disbanding of a bulk of LTTE cadre, other than Karuna’s core supporters. It also drove Karuna

into the arms of the Sri Lanka Army for protection. So when the war started in

the east, the LTTE’s strength as well as its manoeuvring

space was reduced.

In the course of time, recruitment from the east to

augment LTTE strength petered out. Ultimately, when the security forces

launched their offensive in the north with huge numerical superiority, the LTTE

did not have the essential strength to face the onslaught. It was clear that

the LTTE would not be able halt the security forces by conventional warfare.

However, somehow Prabakaran

failed to use his superior insurgency tactics to overcome his limitations in

conventional warfare. Instead, the LTTE adopted a passive defensive strategy

with a line of bunds that reduced the natural advantage of guerilla mobility

enjoyed by the cadre. The bunds imposed a limited delay as they required heavy

firepower to break up the offensive. This was a luxury that the LTTE did not

enjoy.

The second aspect was the LTTE leader’s failure to

read the mind of Rajapaksa. In his first two years in

office, the President had oriented his entire policy framework towards the goal

of eliminating the LTTE. His strong support to the operations of the security

forces, regardless of national and international compulsions, enabled the Army

chief to plan and execute his offensive.

Karuna (right) speaking to women LTTE fighters in Batticaloa district on Women’s Day in March 2004. Prabakaran failed to take into account the impact of Karuna’s defection from the LTTE on its overall military capability.

His strategic direction of war, operational planning

and neat execution undoubtedly paved the way for success. In the words of

Lieutenant General Satish Nambiar,

the distinguished Indian Army officer, Fonseka

“displayed the qualities of a great military leader nations are blessed with

from time to time”. In short, under Fonseka’s

leadership, the demoralised armed forces reinvented

themselves to become a well-knit and highly motivated force.

As a result, when the security forces went to war in

2006, they were well-trained and enjoyed superiority in firepower and mobility.

Learning from the past, they built up force levels on land, in the air and at

sea to ensure success against the Tamil Tigers. The Sri Lanka Army went on a

recruiting spree. For instance, in the year 2008 alone 40,000 troops were

added, to raise 47 infantry battalions, 13 brigades, four task force

contingents and two divisions. The Army now has 13 divisions, three task forces

and one armoured brigade. Evidently, Prabakaran failed to read the sea change taking place in

the capabilities of the security forces and adapt his tactics. Instead, he

stuck to a conventional warfare mode that was doomed to fail although it

inflicted casualties on the advancing troops.

Fonseka adopted a multi-pronged strategy to split the defending Tamil Tiger

ranks and keep them guessing. It aimed at pinning down the LTTE at the

forward-defended localities astride the Kandy-Jaffna A-9 road in the north from

Kilali-Muhamalai-Nagarkovil and in the south along

the Palamoddai-Omanthai line. This prevented the LTTE

from thinning out the troops to reinforce its defences

along other axes.

Offensives along two broad axes were launched: along

the Mannar-Pooneryn/Jaffna A-32 road on the west

coast to block LTTE access to Tamil Nadu through the Mannar

Sea and along the Welioya-Mullaithivu-Puthukudiyiruppu

line on the east coast. Operations on these axes progressively cut off the

external supply of military equipment and essential goods to the LTTE by sea.

In tandem with ground operations, the Sri Lanka Navy progressively curtailed

the freedom of movement of Sea Tiger boats and prevented LTTE shipments from

reaching the Sri Lanka coast. In well-planned raids in international waters,

the Navy destroyed eight ships of the LTTE’s tramp supply shipping fleet in

2006-07.

Despite faltering steps at times, the security forces

maintained the momentum of their offensive in the north from the second half of

2007, which culminated in the dramatic capture in January 2009 of Kilinochchi, the so-called administrative capital of the

LTTE. This capture contributed largely to the rapid advance of the security

forces in areas east of the A-9 axis, which never gave the withdrawing LTTE a

respite or permitted it to deliver a strong counterstroke.

In the present Eelam war,

except for a short-lived surprise offensive in the Jaffna peninsula in the

early stages of the confrontation in the north, the LTTE was never able to

launch proactively a major offensive or a sizable counteroffensive against the

security forces that would have turned the course of the war.

The LTTE strategy of carting off all the civilians

from captured areas to areas under its control after the fall of Kilinochchi is questionable. This reactive defence strategy affected the mobility of cadre, pinning

them down to static defences rather than allowing

them to adopt a resilient mobile withdrawal strategy. This strategy neither

prevented the security forces from using their heavy weapons or air force nor

vindicated the LTTE’s use of civilians as human shields. It only generated

adverse publicity, and that the security forces were also blamed for the same

callousness in dealing with ordinary people is no consolation as they have

emerged as victors.

The performance of the LTTE in Eelam

War IV glaringly displayed Prabakaran’s limitations

in mastering the art of conventional warfare. As he is an astute military

leader, if he survives the current ordeal, he will put on his thinking cap to

reinvent the LTTE, just as Fonseka reinvented the

security forces when he took on the monumental task of reviving them and

leading them to war.

Colonel R. Hariharan is a

retired Military Intelligence specialist on South Asia and served as the head

of intelligence of the Indian Peace Keeping Force in Sri Lanka 1987-90.

உனக்கு

நாடு இல்லை என்றவனைவிட

நமக்கு நாடே இல்லை

என்றவனால்தான்

நான் எனது நாட்டை

விட்டு விரட்டப்பட்டேன்.......

ராஜினி

திரணகம

MBBS(Srilanka)

Phd(Liverpool,

UK)

'அதிர்ச்சி

ஏற்படுத்தும்

சாமர்த்தியம்

விடுதலைப்புலிகளின்

வலிமை மிகுந்த

ஆயுதமாகும்.’ விடுதலைப்புலிகளுடன்

நட்பு பூணுவது

என்பது வினோதமான

சுய தம்பட்டம்

அடிக்கும் விவகாரமே.

விடுதலைப்புலிகளின்

அழைப்பிற்கு உடனே

செவிமடுத்து, மாதக்கணக்கில்

அவர்களின் குழுக்களில்

இருந்து ஆலோசனை

வழங்கி, கடிதங்கள்

வரைந்து, கூட்டங்களில்

பேசித்திரிந்து,

அவர்களுக்கு அடிவருடிகளாக

இருந்தவர்கள்மீது

கூட சூசகமான எச்சரிக்கைகள்,

காலப்போக்கில்

அவர்கள்மீது சந்தேகம்

கொண்டு விடப்பட்டன.........'

(முறிந்த

பனை நூலில் இருந்து)

(இந்

நூலை எழுதிய ராஜினி

திரணகம விடுதலைப்

புலிகளின் புலனாய்வுப்

பிரிவின் முக்கிய

உறுப்பினரான பொஸ்கோ

என்பவரால் 21-9-1989 அன்று

யாழ் பல்கலைக்கழக

வாசலில் வைத்து

சுட்டு கொல்லப்பட்டார்)

Its

capacity to shock was one of the L.T.T.E. smost potent weapons. Friendship with

the L.T.T.E. was a strange and

self-flattering affair.In the course of the coming days dire hints were dropped

for the benefit of several old friends who had for months sat on committees,

given advice, drafted latters, addressed meetings and had placed themselves at

the L.T.T.E.’s beck and call.

From: Broken Palmyra

வடபுலத்

தலமையின் வடஅமெரிக்க

விஜயம்

(சாகரன்)

புலிகளின்

முக்கிய புள்ளி

ஒருவரின் வாக்கு

மூலம்

பிரபாகரனுடன் இறுதி வரை இருந்து முள்ளிவாய்கால் இறுதி சங்காரத்தில் தப்பியவரின் வாக்குமூலம்

திமுக, அதிமுக, தமிழக மக்கள் இவர்களில் வெல்லப் போவது யார்?

(சாகரன்)

தங்கி நிற்க தனி மரம் தேவை! தோப்பு அல்ல!!

(சாகரன்)

(சாகரன்)

வெல்லப்போவது

யார்.....? பாராளுமன்றத்

தேர்தல் 2010

(சாகரன்)

பாராளுமன்றத்

தேர்தல் 2010

தேர்தல்

விஞ்ஞாபனம் - பத்மநாபா

ஈழமக்கள் புரட்சிகர

விடுதலை முன்னணி

1990

முதல் 2009 வரை அட்டைகளின்

(புலிகளின்) ஆட்சியில்......

(fpNwrpad;> ehthe;Jiw)

சமரனின்

ஒரு கைதியின் வரலாறு

'ஆயுதங்கள்

மேல் காதல் கொண்ட

மனநோயாளிகள்.'

வெகு விரைவில்...

மீசை

வைச்ச சிங்களவனும்

ஆசை வைச்ச தமிழனும்

(சாகரன்)

இலங்கையில்

'இராணுவ'

ஆட்சி வேண்டி நிற்கும்

மேற்குலகம், துணை செய்யக்

காத்திருக்கும்;

சரத் பொன்சேகா

கூட்டம்

(சாகரன்)

எமது தெரிவு

எவ்வாறு அமைய வேண்டும்?

பத்மநாபா

ஈபிஆர்எல்எவ்

ஜனாதிபதித்

தேர்தல்

ஆணை இட்ட

அதிபர் 'கை', வேட்டு

வைத்த ஜெனரல்

'துப்பாக்கி' ..... யார் வெல்வார்கள்?

(சாகரன்)

சம்பந்தரே!

உங்களிடம் சில

சந்தேகங்கள்

(சேகர்)

(m. tujuh[g;ngUkhs;)

தொடரும்

60 வருடகால காட்டிக்

கொடுப்பு

ஜனாதிபதித்

தேர்தலில் தமிழ்

மக்கள் பாடம் புகட்டுவார்களா?

(சாகரன்)

ஜனவரி இருபத்தாறு!

விரும்பியோ

விரும்பாமலோ இரு

கட்சிகளுக்குள்

ஒன்றை தமிழ் பேசும்

மக்கள் தேர்ந்தெடுக்க

வேண்டும்.....?

(மோகன்)

2009 விடைபெறுகின்றது!

2010 வரவேற்கின்றது!!

'ஈழத் தமிழ்

பேசும் மக்கள்

மத்தியில் பாசிசத்தின்

உதிர்வும், ஜனநாயகத்தின்

எழுச்சியும்'

(சாகரன்)

மகிந்த ராஜபக்ஷ

& சரத் பொன்சேகா.

(யஹியா

வாஸித்)

கூத்தமைப்பு

கூத்தாடிகளும்

மாற்று தமிழ் அரசியல்

தலைமைகளும்!

(சதா. ஜீ.)

தமிழ்

பேசும் மக்களின்

புதிய அரசியல்

தலைமை

மீண்டும்

திரும்பும் 35 வருடகால

அரசியல் சுழற்சி!

தமிழ் பேசும் மக்களுக்கு

விடிவு கிட்டுமா?

(சாகரன்)

கப்பலோட்டிய

தமிழனும், அகதி

(கப்பல்) தமிழனும்

(சாகரன்)

சூரிச்

மகாநாடு

(பூட்டிய)

இருட்டு அறையில்

கறுப்பு பூனையை

தேடும் முயற்சி

(சாகரன்)

பிரிவோம்!

சந்திப்போம்!!

மீண்டும் சந்திப்போம்!

பிரிவோம்!!

(மோகன்)

தமிழ்

தேசிய கூட்டமைப்புடன்

உறவு

பாம்புக்கு

பால் வார்க்கும்

பழிச் செயல்

(சாகரன்)

இலங்கை

அரசின் முதல் கோணல்

முற்றும் கோணலாக

மாறும் அபாயம்

(சாகரன்)

ஈழ விடுலைப்

போராட்டமும், ஊடகத்துறை

தர்மமும்

(சாகரன்)

(அ.வரதராஜப்பெருமாள்)

மலையகம்

தந்த பாடம்

வடக்கு

கிழக்கு மக்கள்

கற்றுக்கொள்வார்களா?

(சாகரன்)

ஒரு பிரளயம்

கடந்து ஒரு யுகம்

முடிந்தது போல்

சம்பவங்கள் நடந்து

முடிந்துள்ளன.!

(அ.வரதராஜப்பெருமாள்)

அமைதி சமாதானம் ஜனநாயகம்

www.sooddram.com