|

|

Contact us at: sooddram@gmail.com |

A New Battle for Ceylon - Forbes India

(S. Srinivasan)

A group of 43 businessmen from Colombo, Sri Lanka's capital city,

were shocked to see the devastation when they landed in Jaffna in early July. Returning

after three decades, they remembered this palm-fringed peninsula surrounded by

blue lagoons had once been a thriving hub for industry.

As many as 750 small factories churned out everything from household articles

to export items in the 1970s. Now, they were all gone. What greeted them was

broken bridges, burnt homes and families torn by the 26-year-long civil war. Hardly a place to talk business.

The scene elsewhere in the region is no different. The caustic soda factory in Paranthan is in ruins, the Kankesanthurai

cement plant is dysfunctional and Valaichchenai paper

factory has been idle for long.

Even in Colombo, a city living under the constant shadow of terrorism, the mood

is somber. The country came dangerously close to

defaulting on its international payment obligations in March, when its foreign

exchange reserves dipped to a mere $1.3 billion.

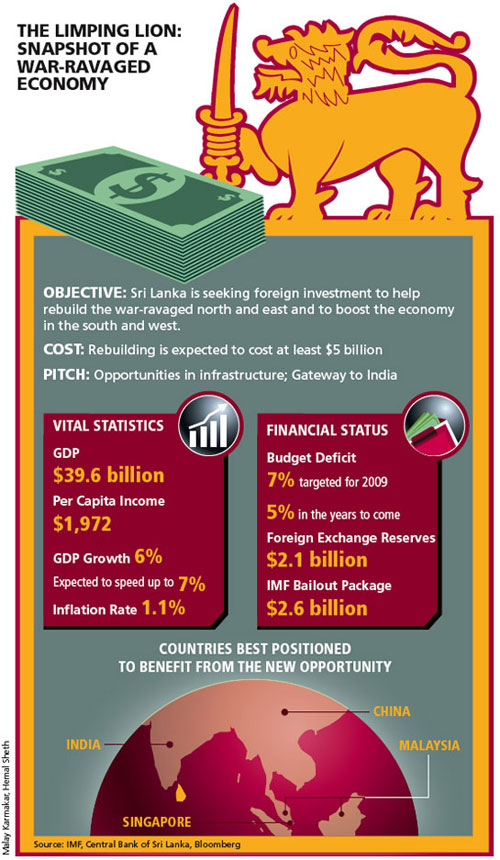

President Mahinda Rajapaksa

rushed to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and got a $2.6 billion bailout

that has imposed strict conditions for fiscal discipline. He will have to raise

taxes and cut expenditure to rein in a whopping 7% budget deficit.

Then, why does investment guru Jim Rogers now recommend Sri Lanka as the

most compelling investment destination?

The answer, simply, is that the civil war is over. The separatist Liberation

Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) has been put down.

The same ruin that kept the embers of despair aglow has now become the spark of

opportunity for the shrewd businessman.

"I have seen that when a long war like this ends, there rise enormous

opportunities for investment," Rogers, co-founder of Quantum Fund and

author of classics such as Investment Biker and Adventure Capitalist, told

Forbes India. "Sri Lanka will need to be rebuilt now and there's little

capital within the country."

Ask Roman Scott. This Singapore based British private equity manager, with

family roots in Sri Lanka, believes the island nation's time has arrived.

"It is going to be one of the best investment opportunities on the

planet for the next two to three years," he says.

His Calamander Group has launched the world's first PE fund exclusively

focussed on Sri Lanka, with a likely corpus of $50-75 million.

Scott says the conflict shaved off 1.5-2.5% from the gross domestic product

(GDP) and even then, Sri Lanka has been the fourth fastest growing economy in

Asia in recent years.

As fighting raged, most foreign investors avoided Lanka and hence there is very

little competition across the business spectrum. Those quick to invest will get

to choose from the business of rebuilding the nation as well as the consumer

market that a healthier society will unleash.

Sizing up the Pie

Just how much money Sri Lanka needs to rebuild itself

is still unknown.

But just the initial investment needed to fix the stalled economy in the north

and east is a $5 billion business, according to government estimates. Roads,

bridges, schools, hospitals, power plants and even homes have to be built

afresh. So, the final tally will be several times larger.

But the sweet spot for the foreign investor is not the war zone. The relatively

peaceful Western Province, where Colombo is located, is a ready market waiting

to be tapped fully.

The infrastructure and a consumer economy are already there, but the war kept

away many providers of goods and services. They will come now. This province,

which accounts for half of Sri Lanka's $40 billion economy, will be the first

to gain from peace.

Scott says Sri Lanka is today in the position that India was in 1991, minus the

war, of course. Colombo has just come out of a foreign exchange crisis, needs

to fix its finances and can very well use the crisis to silence protectionists

and launch economic reforms.

"It has all the potential of India at half the price, with no competition."

In fact, Calamander is especially targetting Indians

for investing in its Lanka fund.

Sri Lanka has traditionally excelled in tea, tourism, garments and rubber.

Business potential in these areas remains, though in niche segments within.

Tea plantations, dominated by trade unions, may not be as attractive anymore

but downstream segments like blending, packaging and branding will be. In the

capital-intensive tourism sector, where payback can take four years or so, the

risk is another terrorist attack will drive away tourists. Apparel export is

crowded and dependent on single large orders.

The new opportunities will not be in the sectors Sri Lanka is known for.

They will be in real estate, business process outsourcing, banking, timber,

pepper, fisheries, education, healthcare and of course, infrastructure.

When the government and LTTE had observed a truce between 2002 and 2005, a wave

of investors reached Sri Lankan shores. With a literacy rate of 97 percent, Sri

Lanka attracted BPO companies,especially

the ones executing accounting tasks. The country has been trying to move into a

services economy too. So, there will be a huge scope for training young people

in manufacturing as well as services businesses.

That is why human resources firm Ma Foi Management

Consultants went there in 2004. "Despite the big need for skills training,

the HR scene there is not well organised," says E. Balaji,

Ma Foi CEO. In fact, most students go to work rather

than go to college. This has led to a shortage of graduates. Also, the official

policy to promote the Sinhala language has weakened English learning in Sri

Lanka over the years, Balaji says.

Government Gets into the Act

Rajapaksa has already taken some steps towards

rebuilding Lanka. He is likely to get an assistance of $300 million from Asian

Development Bank (ADB) for building projects in the war zone. ADB may also give

more funds to help the export-driven economy emerge from the global recession.

Rajapaksa is offering a 15-year tax holiday for

investments in the north and east. He also plans to set up special economic

zones to spur industrial activity. He is keen to get foreign investment and has

dispatched his ministers to various countries to pitch.

There are two reasons why Rajapaksa desperately needs

foreign investors. Capital is expensive in Sri Lanka. Companies borrow at

17-20%. So, rebuilding cannot happen without cheaper capital from outside.

Also, given that his fiscal belt is getting tighter, he has little money to

spare from the coffers.

The natural course for Rajapaksa would be to reform

the economy, bring down interest rates and open up businesses for outsiders.

But his track record is strongly socialist and the Sri Lankan polity generally

favours protectionism.

"There is significant pressure from his own party

and other parties to reverse some of the advances they have made. I don't know

to what extent IMF will really be satisfied," says Jan Zalewski,

a London-based analyst with economic forecasting company IHS Global Insight.

Surviving in Sri Lanka's tentative free market is not easy. A regular business

decision like allowing a fuel pump can become a political row.

Companies from some countries have a natural advantage either because they have

the trust of the Sinhalese or understand the local nuances better.

China falls into the first category and India into the second.

These two countries are likely to play a major role in the reconstruction.

"China, being a large country, is putting a lot of money here. Also,

politically they are not bothered. With India, there were some political

issues. But all that is getting cleaned," says Chandra Lal de Alwis, president of the National Chamber of Commerce of Sri

Lanka, which sent the business delegation to Jaffna.

Big Brother Is Coming

India has already started pumping hundreds of millions of dollars into Sri

Lanka for the rehabilitation of 280,000 internally displaced persons living in

government camps. But more importantly, companies, including public sector

units, (PSUs) are queuing up to invest big time.

The National Thermal Power Corporation plans a 500 megawatt, $500 million power

plant in a joint venture with Ceylon Electricity Board. This will be one-fifth

of the country's total capacity currently. Another Indian PSU, Power GridCorporation, wants to set up an undersea transmission

link between the two countries.

Construction and engineering giant Larsen & Toubro (L&T) will surely

play a big role in the post-conflict construction. A most symbolic venture is

Sri Lanka's tallest building (59 storeys) being built in Colombo by an L&T

joint venture.

India's largest enterprise, Indian Oil Corporation (IOC), runs about 150 fuel

stations in Sri Lanka, the country's largest storage facility, an oil terminal

and a lubricant blending plant. It is eyeing network expansion and new business

segments.

Ashok Leyland trucks and Hero Honda vehicles are already popular and they have

plans to further penetrate the market. Asian Paints, which runs a 5,500

kilolitre facility, sees the tiny market for its products booming in the coming

years and is expanding accordingly.

Bharti Airtel, which

entered the island with its mobile phone services last year, has already

invested $250 million and a like sum is on its way. The list of Indian

companies lining up investments in Sri Lanka is long and impressive.

But not everyone is happy. The inwardlooking economic

stance of politicians has often come in the way of business decisions.

For instance, Lanka IOC has not been given the freedom to expand its fuelpump network or get into new segments like selling

aviation fuel. The company was locked in a dispute over subsidy payment it was

owed. "We need to be given more opportunities," says K.R. Suresh

Kumar, managing director of Lanka IOC. "There is a clarity required in

terms of economic policy. There is some sense of reforms. But they seem to go

back in time. Th e fear of losing control of

state-run companies should go away," he says.

The agreement for NTPC's power project has also been

delayed over questions on payment security.

Weighing the Risks

What can go wrong for foreign investors in Sri Lanka? A return of violence or restrictive policies.

Analyst Zalewski says the risk of violence will not

go away unless Rajapaksa solves the underlying

problem of Tamils and gives them equal rights.

But Calamander's Scott thinks the government has effectively contained the

Tigers and the risk of violence is very low. Even the suppression of free

expression by Rajapaksa's government, while

condemnable, will not affect business, he says. "Sadly, economics and

democratic principles are not really that strongly related."

All said, Sri Lanka has two choices today.

It can shrink back into a protectionist regime and miss this historic

opportunity to become an economic power. Or, it can take foreign capital and

expertise to rebuild itself, solve the ethnic problem, add the Tamil population

to the work force and forget violence forever.

This article appears in the August 28 issue of Forbes India, a Forbes Media

licensee.

உனக்கு

நாடு இல்லை என்றவனைவிட

நமக்கு நாடே இல்லை

என்றவனால்தான்

நான் எனது நாட்டை

விட்டு விரட்டப்பட்டேன்.......

ராஜினி

திரணகம

MBBS(Srilanka)

Phd(Liverpool,

UK)

'அதிர்ச்சி

ஏற்படுத்தும்

சாமர்த்தியம்

விடுதலைப்புலிகளின்

வலிமை மிகுந்த

ஆயுதமாகும்.’ விடுதலைப்புலிகளுடன்

நட்பு பூணுவது

என்பது வினோதமான

சுய தம்பட்டம்

அடிக்கும் விவகாரமே.

விடுதலைப்புலிகளின்

அழைப்பிற்கு உடனே

செவிமடுத்து, மாதக்கணக்கில்

அவர்களின் குழுக்களில்

இருந்து ஆலோசனை

வழங்கி, கடிதங்கள்

வரைந்து, கூட்டங்களில்

பேசித்திரிந்து,

அவர்களுக்கு அடிவருடிகளாக

இருந்தவர்கள்மீது

கூட சூசகமான எச்சரிக்கைகள்,

காலப்போக்கில்

அவர்கள்மீது சந்தேகம்

கொண்டு விடப்பட்டன.........'

(முறிந்த

பனை நூலில் இருந்து)

(இந்

நூலை எழுதிய ராஜினி

திரணகம விடுதலைப்

புலிகளின் புலனாய்வுப்

பிரிவின் முக்கிய

உறுப்பினரான பொஸ்கோ

என்பவரால் 21-9-1989 அன்று

யாழ் பல்கலைக்கழக

வாசலில் வைத்து

சுட்டு கொல்லப்பட்டார்)

Its

capacity to shock was one of the L.T.T.E. smost potent weapons. Friendship with

the L.T.T.E. was a strange and

self-flattering affair.In the course of the coming days dire hints were dropped

for the benefit of several old friends who had for months sat on committees,

given advice, drafted latters, addressed meetings and had placed themselves at

the L.T.T.E.’s beck and call.

From: Broken Palmyra

வடபுலத்

தலமையின் வடஅமெரிக்க

விஜயம்

(சாகரன்)

புலிகளின்

முக்கிய புள்ளி

ஒருவரின் வாக்கு

மூலம்

பிரபாகரனுடன் இறுதி வரை இருந்து முள்ளிவாய்கால் இறுதி சங்காரத்தில் தப்பியவரின் வாக்குமூலம்

திமுக, அதிமுக, தமிழக மக்கள் இவர்களில் வெல்லப் போவது யார்?

(சாகரன்)

தங்கி நிற்க தனி மரம் தேவை! தோப்பு அல்ல!!

(சாகரன்)

(சாகரன்)

வெல்லப்போவது

யார்.....? பாராளுமன்றத்

தேர்தல் 2010

(சாகரன்)

பாராளுமன்றத்

தேர்தல் 2010

தேர்தல்

விஞ்ஞாபனம் - பத்மநாபா

ஈழமக்கள் புரட்சிகர

விடுதலை முன்னணி

1990

முதல் 2009 வரை அட்டைகளின்

(புலிகளின்) ஆட்சியில்......

(fpNwrpad;> ehthe;Jiw)

சமரனின்

ஒரு கைதியின் வரலாறு

'ஆயுதங்கள்

மேல் காதல் கொண்ட

மனநோயாளிகள்.'

வெகு விரைவில்...

மீசை

வைச்ச சிங்களவனும்

ஆசை வைச்ச தமிழனும்

(சாகரன்)

இலங்கையில்

'இராணுவ'

ஆட்சி வேண்டி நிற்கும்

மேற்குலகம், துணை செய்யக்

காத்திருக்கும்;

சரத் பொன்சேகா

கூட்டம்

(சாகரன்)

எமது தெரிவு

எவ்வாறு அமைய வேண்டும்?

பத்மநாபா

ஈபிஆர்எல்எவ்

ஜனாதிபதித்

தேர்தல்

ஆணை இட்ட

அதிபர் 'கை', வேட்டு

வைத்த ஜெனரல்

'துப்பாக்கி' ..... யார் வெல்வார்கள்?

(சாகரன்)

சம்பந்தரே!

உங்களிடம் சில

சந்தேகங்கள்

(சேகர்)

(m. tujuh[g;ngUkhs;)

தொடரும்

60 வருடகால காட்டிக்

கொடுப்பு

ஜனாதிபதித்

தேர்தலில் தமிழ்

மக்கள் பாடம் புகட்டுவார்களா?

(சாகரன்)

ஜனவரி இருபத்தாறு!

விரும்பியோ

விரும்பாமலோ இரு

கட்சிகளுக்குள்

ஒன்றை தமிழ் பேசும்

மக்கள் தேர்ந்தெடுக்க

வேண்டும்.....?

(மோகன்)

2009 விடைபெறுகின்றது!

2010 வரவேற்கின்றது!!

'ஈழத் தமிழ்

பேசும் மக்கள்

மத்தியில் பாசிசத்தின்

உதிர்வும், ஜனநாயகத்தின்

எழுச்சியும்'

(சாகரன்)

மகிந்த ராஜபக்ஷ

& சரத் பொன்சேகா.

(யஹியா

வாஸித்)

கூத்தமைப்பு

கூத்தாடிகளும்

மாற்று தமிழ் அரசியல்

தலைமைகளும்!

(சதா. ஜீ.)

தமிழ்

பேசும் மக்களின்

புதிய அரசியல்

தலைமை

மீண்டும்

திரும்பும் 35 வருடகால

அரசியல் சுழற்சி!

தமிழ் பேசும் மக்களுக்கு

விடிவு கிட்டுமா?

(சாகரன்)

கப்பலோட்டிய

தமிழனும், அகதி

(கப்பல்) தமிழனும்

(சாகரன்)

சூரிச்

மகாநாடு

(பூட்டிய)

இருட்டு அறையில்

கறுப்பு பூனையை

தேடும் முயற்சி

(சாகரன்)

பிரிவோம்!

சந்திப்போம்!!

மீண்டும் சந்திப்போம்!

பிரிவோம்!!

(மோகன்)

தமிழ்

தேசிய கூட்டமைப்புடன்

உறவு

பாம்புக்கு

பால் வார்க்கும்

பழிச் செயல்

(சாகரன்)

இலங்கை

அரசின் முதல் கோணல்

முற்றும் கோணலாக

மாறும் அபாயம்

(சாகரன்)

ஈழ விடுலைப்

போராட்டமும், ஊடகத்துறை

தர்மமும்

(சாகரன்)

(அ.வரதராஜப்பெருமாள்)

மலையகம்

தந்த பாடம்

வடக்கு

கிழக்கு மக்கள்

கற்றுக்கொள்வார்களா?

(சாகரன்)

ஒரு பிரளயம்

கடந்து ஒரு யுகம்

முடிந்தது போல்

சம்பவங்கள் நடந்து

முடிந்துள்ளன.!

(அ.வரதராஜப்பெருமாள்)

அமைதி சமாதானம் ஜனநாயகம்

www.sooddram.com