|

|

Contact us at: sooddram@gmail.com |

What next?

|

Once the war is over, President

Mahinda Rajakapsa must evolve a political solution acceptable to all parties

to the conflict. |

N. RAM

B. MURALIDHAR REDDY

Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and Sri Lankan President J.R. Jayewardene sign

the historic India-Sri Lanka Accord in Colombo on July 29, 1987.

WHAT next? That seems to be the

question Sri Lanka watchers are asking as the defences of the Liberation Tigers

of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) collapse like ninepins in the face of the aggressive

military assault in the Wanni.

It would be a mistake, however, to

presume that the ethnic conflict will cease once the LTTE is reduced to an

entity without a defined territory for the first time since the departure of

the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) in March 1990. The LTTE is expected to

retain its capabilities as a guerilla outfit, though how effective it will be

remains to be seen. The ethnic conflict goes back deeper into the past than the

LTTE. Indeed, the LTTE led by Velupillai Prabakaran came into being two decades

after the Official Language Act, No. 33 of 1956 deepened the Tamil-Sinhala

divide with its mandate that Sinhala was the “one official language” of what

was then Ceylon.

The LTTE, now notorious for its

brutalities against anyone it perceives to be an adversary, is a by-product of

the real and perceived grievances of Tamils and other minorities in the

overwhelmingly Sinhala island nation. That a legitimate demand of Sri Lankan

Tamils for the recognition of their language on a par with Sinhala was allowed

to take the form of a movement for a separate state speaks volumes of the

insensitive approach of the parties representing the majority community in

handling the problems of a multilingual, multi-religious and multi-ethnic

society.

Sixty-one years after the country

was granted independence by the British, the ruling elite seems to have learnt

nothing from the pre- or post-colonial experiences of the island nation.

Indeed, long before the British left Sri Lanka in 1948, there were already

enough indications of the apprehensions and anxieties of the minorities in general,

and Tamils in particular, on their fate in a free country in which 75 per cent

of the population belonged to one community.

Ketheshwaran Loganathan, the Deputy

Secretary-General of the Sri Lanka Peace Secretariat who was murdered in late

2006 by suspected LTTE cadre, wrote in his memorable book Sri Lanka: Lost

Opportunities: “The demand by the principal Tamil political party at the

dawn of independence, the All Ceylon Tamil Congress [ACTC], for ‘balanced

representation’ or the ‘50-50 formula’ [50 per cent of the seats to the

Sinhalese majority and 50 per cent to the ethnic minorities, including a

mandatory representation of the minorities in the Cabinet] was a clear

manifestation of the preference for power-sharing at the Centre, as a means of

safeguarding minority rights.”

The Soulbury Commission constituted

by the British to draw up the post-independent Constitution took the view that

a 50-50 formula would be fatal to the emergence of that unquestioning sense of

nationhood necessary for the exercise of full self-government. However, the

commission inserted a safeguard clause that prohibited the passage of any piece

of legislation rendering persons of any community or religion liable to

disabilities. The ACTC demand could be construed as the maximalist demand by

the minorities in the hope of securing the best deal.

HOHD ILYAS

RAJIV GANDHI'S ASSASSINATION on May 21, 1991, marked the end of the enormous

goodwill that the Sri Lankan Tamil cause enjoyed in Tamil Nadu in the 1980s.

Here, the body of Rajiv Gandhi being carried to Teen Murti House in New Delhi

the day after the assassination.

Incidentally, one of the first acts

of the parliament of the newly independent Ceylon was to disenfranchise

hundreds of thousands of Tamils of Indian origin, or up-country Tamils. These

were the people brought by the British as indentured labour to work on the

coffee/tea plantations in the hill districts. It is one of the ironies of

history that Sri Lankan Tamils voted with the majority community to deny

citizenship rights to Tamils of Indian origin.

The moment of truth arrived for Sri

Lankan Tamils when the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) government led by

S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike got parliament to adopt a law making Sinhala the only

official language. What S.V.J. Chelvanayagam, founder of the ACTC, said when

the second reading of the Citizenship Rights of Indian Origin people came for

up discussion in 1948, turned out to be prophetic: “He [Prime Minister

Senanayake] is not hitting us now directly but when the language question comes

up, we will know where we stand. Perhaps that will not be the end of it.”

The Official Language Act, No. 33

proved to be a turning point in the ethnic conflict. It got worse with every

passing year. Successive governments entered into agreements with the Tamils

parties – the Bandaranaike-Chelvanayagam agreement and the

Senanayake-Chelvanayagam agreement, for instance – to undo the impact of the

“Sinhala only” legislation but only to retreat under pressure from majority

lobbies.

Recorded history shows that Tamil

parties resorted to every conceivable method of agitation in the democratic way

from 1956 to 1976. What the Tamil minority saw as the “colonisation” of the

Tamil-majority north and east by the Sinhala-dominated state emerged as another

bone of contention, apart from the language issue. The Tamil parties alleged

that successive governments in Colombo were systematically settling Sinhalese

people in the north and the east in order to alter the demography in favour of

the majority community.

The parties in government reasoned

that 12.5 per cent of the population inhabited the two regions which together

accounted for 30 per cent of the island’s landmass and 60 per cent of its

coastline and it was unfair for this small percentage of the population to lay

exclusive claim to the resources of the two regions. The Tamil parties’

argument that local residents should be given preference in allotment of lands

brought under new irrigation facilities amounted to the “son of the soil”

theory, according to them.

Indeed, the Tamil parties’ argument

on the alleged “colonisation” does not hold water because of two factors.

Though there are no precise figures, most political observers agree that over

50 per cent of Tamils in Sri Lanka live outside the Northern and Eastern

provinces. Besides, even according to the pro-LTTE Tamil National Alliance

(TNA), despite the “massive colonisation” schemes of successive governments,

the total percentage of Sinhalese people in the North and the East is below 3

per cent. Actually there are no Sinhalese people living in the North barring a

dozen who married Tamils and settled in the Jaffna peninsula.

The procrastination on the part of

successive governments over granting equal status to the Tamil language, and

over other grievances, including that on the question of devolution of powers,

led to two important developments in 1976. The Tamil parties, under the banner

of the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF), articulated the demand for a

separate state of Tamil Eelam. Around the same time, Tamil militancy was taking

root. The LTTE was among the dozen-odd militant outfits that emerged.

The Vadukodai Resolution, adopted at

the first National Convention of the TULF on May 14, 1976, said:

“Whereas, throughout the centuries

from the dawn of history, the Sinhalese and Tamil nations have divided between

themselves the possession of Ceylon, the Sinhalese inhabiting the interior of

the country in its Southern and Western parts from the river Walawe to that of

Chilaw and the Tamils possessing the Northern and Eastern districts; …

HINDU

PHOTO LIBRARY

PRIME MINISTER S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike (left) and S.J.V. Chelvanayagam, leader

of the Thamil Arasu Katchi, shake hands after signing what came to be known as

the Bandaranaike-Chelvanayagam Pact on July 26, 1957. Bandaranaike repudiated

the agreement in April 1958 in view of a campaign led by the Buddhist clergy

and sections of the Sinhala political leadership, including Jayewardene, who

was then Leader of the Opposition.

“That the State of Tamil Eelam shall

consist of the people of the Northern and Eastern provinces and shall also

ensure full and equal rights of citizenship of the State of Tamil Eelam to all

Tamil-speaking people living in any part of Ceylon and to Tamils of Eelam

origin living in any part of the world who may opt for citizenship of Tamil

Eelam.”

The TULF participated in the 1977

general elections on the basis of that resolution. The LTTE has consistently

stuck to the demand for Tamil Eelam, and the only occasion on which it

indicated a willingness to explore the possibility of a solution within a

united Sri Lanka was in December 2002, nearly 10 months after it signed a Cease

Fire Agreement (CFA) with the Ranil Wickremasinghe government. The Oslo

Declaration, as it is known, read: “Responding to a proposal by the leadership

of the LTTE, the parties agreed to explore a solution founded on the principle

of internal self-determination in areas of historical habitation of the

Tamil-speaking peoples, based on a federal structure within a united Sri Lanka.

The parties acknowledged that the solution has to be acceptable to all

communities.” But the LTTE distanced itself from the Oslo Declaration within a

few months.

The early 1980s saw indirect Indian

intervention in the conflict as several training camps were set up for the Sri

Lanka Tamil militant groups. The perceived pro-Western tilt in the J.R.

Jayewardene government’s foreign policy was cited as justification for Indian

help to the militant groups by the Indira Gandhi government. The 1983 pogrom,

in which 2,000 Tamils were killed in Colombo alone, not only left a deep scar

on the psyche of Sri Lankan Tamils but also triggered unprecedented waves of

emotional outbursts among the diaspora in general and in Tamil Nadu in

particular in support of the Tamil cause. (The brutal murder of Rajiv Gandhi in

1991 by an LTTE suicide bomber in Sriperumbudur marked the end of the enormous

goodwill that the Sri Lankan Tamil cause enjoyed in Tamil Nadu.)

India’s policy towards Sri Lanka

changed dramatically under Rajiv Gandhi’s prime ministership. India’s efforts

were now directed towards helping Sri Lanka to find a political solution to the

ethnic problem, and the result was the 1985 Thimphu talks. A joint statement

issued at the conference on July 13, 1985, by the Joint Front of the Tamil

Liberation Organisations, a platform under which for the first time all the

political and militant outfits came together, laying down what was termed as

“four cardinal principals” for the basis of any meaningful solution, brought to

the fore the growing determination of Tamils to attain a separate state.

The four cardinal principles were –

“Recognition of the Tamils of Sri Lanka as a distinct nationality, recognition

of an identified Tamil homeland and the guarantee of the territorial integrity,

based on the above, recognition of inalienable right of self-determination of

the Tamil nation and recognition of the right to full citizenship and other fundamental

democratic rights of all Tamils, who look upon the island as their country.”

The Jayewardene government saw them

as the first step towards formation of a separate Tamil Eelam and rejected them

outright. India concurred with the Sri Lankan government’s view but continued

its efforts to bring about a political settlement acceptable to all sections.

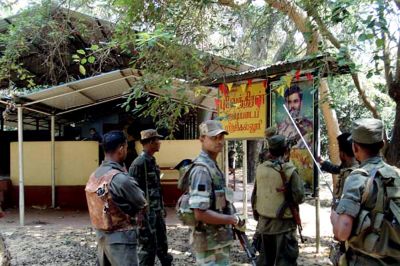

SOLDIERS OUTSIDE A camp believed to have been used to train Black Tiger

suicide bombers in Mullaithivu district. The photograph was released on

February 4 by the Ministry of Defence, which said the training facility was

captured on the previous day.

After two years of tortuous and

intense negotiations came the 1987 India-Sri Lanka Accord, signed by Rajiv

Gandhi and Jayewardene in Colombo on July 29, 1987. The accord, for the first

time, laid down a comprehensive framework to redress the grievances of Tamils

and other minorities. The LTTE, which is believed to have given its tacit

approval when the accord was being crafted, did a U-turn at the last minute and

became the only militant outfit to reject it.

The accord acknowledges the unity,

sovereignty and territorial integrity of Sri Lanka and the multi-ethnic and

multilingual character of the island nation, recognising that each ethnic group

has a distinct cultural and linguistic identity which must be carefully

nurtured.

The accord bound the Sri Lankan

government to the position that the Northern and the Eastern provinces had been

areas of “historical habitation of Sri Lankan Tamil-speaking peoples” and paved

the way for a temporary merger of the North and the East into a single

province, subject to a referendum within a year.

The agreement on the merger and the

referendum was based on the assumption that all militant groups would lay down

arms and create the right atmosphere for peace and the rule of law. India,

which guaranteed the provisions of the accord, sent the IPKF to the island,

only to end up as the villain of the piece. The IPKF left the island two and a

half years later after losing some 1,300 soldiers and officers in the fight

against the LTTE.

Ironically, Ranasinghe Premadasa’s

government joined hands with the LTTE to secure the withdrawal of the IPKF. India

chose to adopt a hands-off policy with regard to Sri Lanka after the

assassination of Rajiv Gandhi in May 1991. The 1987 accord and the 13th

Amendment to the Sri Lanka Constitution flowing out of it remain unimplemented

to this day. There have been all kinds of experiments and formulas since that

accord, but none helped to end the conflict.

Now, with the Tigers on the verge of

a humiliating defeat, the Mahinda Rajapaksa government is faced with the

challenge of winning the hearts and minds of the minorities. In the immediate

and medium term, the challenge is to rehabilitate the hundreds of thousands of

displaced people. These people belong to several categories. There are, for

instance, some 80,000 Muslims who were exiled by the LTTE from the Jaffna peninsula

in the late 1990s at less than 24 hours’ notice. They have been languishing in

makeshift camps for 18 years.

In the long run, Rajapaksa must work

on a political solution that is acceptable to all parties. Given the politics

of opportunism and blind opposition practised for decades by various parties

representing the majority community, it is not an easy task. The vacuum created

in the north with the imminent decline of the LTTE will probably be filled by a

number of Tamil militant–turned-political outfits that were hounded by the

Tigers after the latter took control of the north in 1990. As Tamil Nadu Chief

Minister M. Karunanidhi observed at his party’s Executive Committee in Chennai

on February 3, disunity and fratricidal politics have been the hallmark of

Tamil militant groups and parties.

For the record, President Rajapaksa

is talking of his intention to move as quickly as possible to implement the

13th Amendment. He told External Affairs Minister Pranab Mukherjee, who was on

an unscheduled visit to the island on the evening of January 27, that he would

explore the possibility of going further and improving upon those devolution

proposals.

The deep wounds of the conflict will

not be healed easily. The process will require a serious and sincere effort to

reach out to the minorities, including the Sri Lankan Tamil diaspora, and

reassure them that their dignity and honour, language(s), culture and ways of

life will be protected and nurtured. Triumphalism will be disastrous.•

(Frontline)

உனக்கு

நாடு இல்லை என்றவனைவிட

நமக்கு நாடே இல்லை

என்றவனால்தான்

நான் எனது நாட்டை

விட்டு விரட்டப்பட்டேன்.......

ராஜினி

திரணகம

MBBS(Srilanka)

Phd(Liverpool,

UK)

'அதிர்ச்சி

ஏற்படுத்தும்

சாமர்த்தியம்

விடுதலைப்புலிகளின்

வலிமை மிகுந்த

ஆயுதமாகும்.’ விடுதலைப்புலிகளுடன்

நட்பு பூணுவது

என்பது வினோதமான

சுய தம்பட்டம்

அடிக்கும் விவகாரமே.

விடுதலைப்புலிகளின்

அழைப்பிற்கு உடனே

செவிமடுத்து, மாதக்கணக்கில்

அவர்களின் குழுக்களில்

இருந்து ஆலோசனை

வழங்கி, கடிதங்கள்

வரைந்து, கூட்டங்களில்

பேசித்திரிந்து,

அவர்களுக்கு அடிவருடிகளாக

இருந்தவர்கள்மீது

கூட சூசகமான எச்சரிக்கைகள்,

காலப்போக்கில்

அவர்கள்மீது சந்தேகம்

கொண்டு விடப்பட்டன.........'

(முறிந்த

பனை நூலில் இருந்து)

(இந்

நூலை எழுதிய ராஜினி

திரணகம விடுதலைப்

புலிகளின் புலனாய்வுப்

பிரிவின் முக்கிய

உறுப்பினரான பொஸ்கோ

என்பவரால் 21-9-1989 அன்று

யாழ் பல்கலைக்கழக

வாசலில் வைத்து

சுட்டு கொல்லப்பட்டார்)

Its

capacity to shock was one of the L.T.T.E. smost potent weapons. Friendship with

the L.T.T.E. was a strange and

self-flattering affair.In the course of the coming days dire hints were dropped

for the benefit of several old friends who had for months sat on committees,

given advice, drafted latters, addressed meetings and had placed themselves at

the L.T.T.E.’s beck and call.

From: Broken Palmyra

வடபுலத்

தலமையின் வடஅமெரிக்க

விஜயம்

(சாகரன்)

புலிகளின்

முக்கிய புள்ளி

ஒருவரின் வாக்கு

மூலம்

பிரபாகரனுடன் இறுதி வரை இருந்து முள்ளிவாய்கால் இறுதி சங்காரத்தில் தப்பியவரின் வாக்குமூலம்

திமுக, அதிமுக, தமிழக மக்கள் இவர்களில் வெல்லப் போவது யார்?

(சாகரன்)

தங்கி நிற்க தனி மரம் தேவை! தோப்பு அல்ல!!

(சாகரன்)

(சாகரன்)

வெல்லப்போவது

யார்.....? பாராளுமன்றத்

தேர்தல் 2010

(சாகரன்)

பாராளுமன்றத்

தேர்தல் 2010

தேர்தல்

விஞ்ஞாபனம் - பத்மநாபா

ஈழமக்கள் புரட்சிகர

விடுதலை முன்னணி

1990

முதல் 2009 வரை அட்டைகளின்

(புலிகளின்) ஆட்சியில்......

(fpNwrpad;> ehthe;Jiw)

சமரனின்

ஒரு கைதியின் வரலாறு

'ஆயுதங்கள்

மேல் காதல் கொண்ட

மனநோயாளிகள்.'

வெகு விரைவில்...

மீசை

வைச்ச சிங்களவனும்

ஆசை வைச்ச தமிழனும்

(சாகரன்)

இலங்கையில்

'இராணுவ'

ஆட்சி வேண்டி நிற்கும்

மேற்குலகம், துணை செய்யக்

காத்திருக்கும்;

சரத் பொன்சேகா

கூட்டம்

(சாகரன்)

எமது தெரிவு

எவ்வாறு அமைய வேண்டும்?

பத்மநாபா

ஈபிஆர்எல்எவ்

ஜனாதிபதித்

தேர்தல்

ஆணை இட்ட

அதிபர் 'கை', வேட்டு

வைத்த ஜெனரல்

'துப்பாக்கி' ..... யார் வெல்வார்கள்?

(சாகரன்)

சம்பந்தரே!

உங்களிடம் சில

சந்தேகங்கள்

(சேகர்)

(m. tujuh[g;ngUkhs;)

தொடரும்

60 வருடகால காட்டிக்

கொடுப்பு

ஜனாதிபதித்

தேர்தலில் தமிழ்

மக்கள் பாடம் புகட்டுவார்களா?

(சாகரன்)

ஜனவரி இருபத்தாறு!

விரும்பியோ

விரும்பாமலோ இரு

கட்சிகளுக்குள்

ஒன்றை தமிழ் பேசும்

மக்கள் தேர்ந்தெடுக்க

வேண்டும்.....?

(மோகன்)

2009 விடைபெறுகின்றது!

2010 வரவேற்கின்றது!!

'ஈழத் தமிழ்

பேசும் மக்கள்

மத்தியில் பாசிசத்தின்

உதிர்வும், ஜனநாயகத்தின்

எழுச்சியும்'

(சாகரன்)

மகிந்த ராஜபக்ஷ

& சரத் பொன்சேகா.

(யஹியா

வாஸித்)

கூத்தமைப்பு

கூத்தாடிகளும்

மாற்று தமிழ் அரசியல்

தலைமைகளும்!

(சதா. ஜீ.)

தமிழ்

பேசும் மக்களின்

புதிய அரசியல்

தலைமை

மீண்டும்

திரும்பும் 35 வருடகால

அரசியல் சுழற்சி!

தமிழ் பேசும் மக்களுக்கு

விடிவு கிட்டுமா?

(சாகரன்)

கப்பலோட்டிய

தமிழனும், அகதி

(கப்பல்) தமிழனும்

(சாகரன்)

சூரிச்

மகாநாடு

(பூட்டிய)

இருட்டு அறையில்

கறுப்பு பூனையை

தேடும் முயற்சி

(சாகரன்)

பிரிவோம்!

சந்திப்போம்!!

மீண்டும் சந்திப்போம்!

பிரிவோம்!!

(மோகன்)

தமிழ்

தேசிய கூட்டமைப்புடன்

உறவு

பாம்புக்கு

பால் வார்க்கும்

பழிச் செயல்

(சாகரன்)

இலங்கை

அரசின் முதல் கோணல்

முற்றும் கோணலாக

மாறும் அபாயம்

(சாகரன்)

ஈழ விடுலைப்

போராட்டமும், ஊடகத்துறை

தர்மமும்

(சாகரன்)

(அ.வரதராஜப்பெருமாள்)

மலையகம்

தந்த பாடம்

வடக்கு

கிழக்கு மக்கள்

கற்றுக்கொள்வார்களா?

(சாகரன்)

ஒரு பிரளயம்

கடந்து ஒரு யுகம்

முடிந்தது போல்

சம்பவங்கள் நடந்து

முடிந்துள்ளன.!

(அ.வரதராஜப்பெருமாள்)

அமைதி சமாதானம் ஜனநாயகம்

www.sooddram.com